People are using intermittent fasting as a common dietary strategy to help them reduce or maintain their weight. Moreover, it has been marketed as a means of resetting metabolism, managing chronic illnesses, delaying aging, and enhancing general health. Intermittent fasting, however, may offer the brain an alternative energy source and offer defense against neurodegenerative illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease, according to some research.

Understanding Intermittent Fasting

We have the ability to modify certain aspects of our lifestyle, such as the number of calories we consume, the timing of our meals, and the makeup of our macronutrients (the amounts of fat, protein, and carbs we eat). People engage in this behavior for cultural, weight-loss, or potential health benefits.

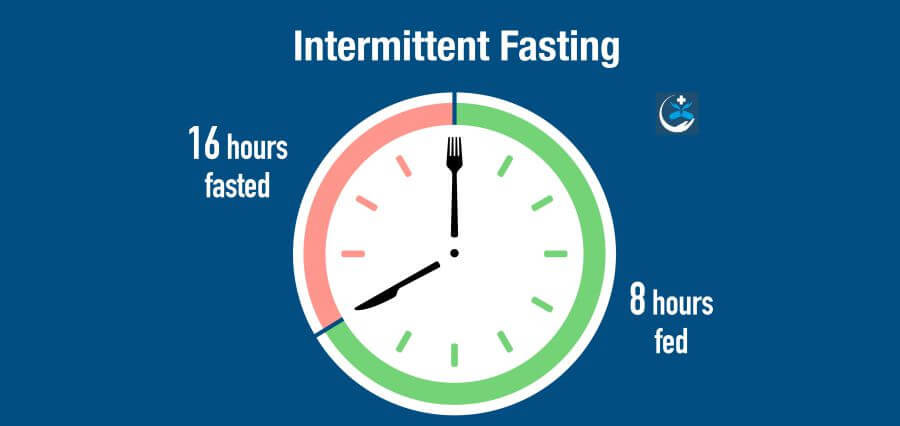

A brief period of calorie (energy) restriction, lasting 12 to 48 hours (typically 12 to 16 hours each day), is interspersed with regular eating intervals to form intermittent fasting. The term “intermittent” refers to a pattern that recurs rather than a “one off” fast.

If you go without food for more than twenty-four hours, you are probably starving. This differs from fasting because it causes unique, possibly hazardous metabolic changes and food shortages if prolonged.

Four mechanisms of action and potential brain effects of fasting Approximately 20% of the body’s energy is used by the brain.

These four physiological aspects of intermittent fasting may help to explain its possible effects on the brain.

1. Ketosis

Many intermittent fasting regimens aim to turn on a “metabolic switch” that shifts the body’s primary energy source from burning carbohydrates to burning fat. This is known as ketosis, and it usually happens after a fast of 12 to 16 hours, during which time the liver and glycogen stores are exhausted. The molecules called ketones, which are created during this metabolic process, end up becoming the brain’s favoured energy source.

As a result of its slower metabolic process for generating energy and tendency to drop blood sugar, hunger, exhaustion, nausea, depression, irritability, constipation, migraines, and “fog” in the brain are some of the symptoms associated with ketosis.

Studies have demonstrated that ketones may offer an alternate energy source to maintain brain function and fend off age-related neurodegenerative problems and cognitive decline, just as the brain’s ability to metabolize glucose diminishes with aging.

In line with this, it has been demonstrated that raising ketones through diet or supplementation improves cognition in persons at risk of Alzheimer’s disease and moderate cognitive decline, respectively.

- Circadian syncing

Eating outside of our bodies’ regular cycles can cause havoc with organ function. Research on shift workers has indicated that this may also increase our vulnerability to chronic illnesses.

Eating inside a six- to ten-hour window during the day when you’re most active is known as time-restricted eating. Eating within a time constraint alters the way genes are expressed in tissue and supports the body throughout both activity and rest.

According to a 2021 study conducted in Italy on 883 adults, those who limited their daily meal intake to 10 hours had a lower risk of cognitive impairment than those who did not.

- Mitochondria

By enhancing metabolism, lowering oxidants, and enhancing mitochondrial function, intermittent fasting may protect the brain.

The primary function of mitochondria is energy production, and they are essential to brain function. An imbalance in the supply and demand of energy, which is most likely caused by mitochondrial failure as we age, is intimately linked to a number of age-related disorders.

Studies on rodents indicate that cutting calories by up to 40% or fasting on alternate days may preserve or enhance mitochondrial activity in the brain. Yet not every study lends credence to this idea.

- The gut-brain axis

The neurological systems of the body facilitate communication between the brain and the gut. The gut can impact mood, cognition, and mental health, and the brain can affect how the gut feels (consider how being anxious can make you feel like you have “butterflies” in your stomach).

Intermittent fasting in mice has demonstrated potential to enhance brain function by promoting the survival and development of neurons, or nerve cells, in the hippocampus brain region—a region linked to memory, learning, and emotion.

The consequences of intermittent fasting on healthy adult cognition are not well-established. Nonetheless, a 2022 study that included 411 older persons discovered a correlation between a decreased meal frequency—less than three meals per day—and a decrease in the amount of Alzheimer’s disease evidence visible on brain imaging.

According to some research, cutting calories may help prevent Alzheimer’s by lowering inflammation and oxidative stress while improving vascular health.

The research is conflicting when it comes to the consequences of general energy restriction as opposed to intermittent fasting in particular. In one study, participants who followed a calorie-restricted diet for a full year demonstrated improvements in cognitive function among those with mild cognitive impairment.

A 25% calorie restriction was linked to marginally better working memory in healthy people, according to another study. However, a recent study that examined how calorie restriction affected spatial working memory did not find any discernible effects.

Intermittent fasting has been shown to improve brain function and slow down the aging process in animals, but there are few and inconsistent research on people.

Particularly in older persons whose nutritional needs may be higher, rapid weight loss linked to calorie restriction and intermittent fasting can result in vitamin shortages, muscle loss, and weakened immune systems.